When the packed auditorium sang “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” at the end of Founder’s Week in 1956, no one was particularly surprised. Then, as now, the hymn was enormously popular at Moody Bible Institute, one of those songs that everyone memorized, right down to the four-part harmony. But songleader Alfred B. Smith ’36 had planned a special tribute that year, inviting the composer back to campus for a curtain call of sorts, which explained why a frail, white-haired gentleman stood in the front row, unashamedly weeping while his best-known hymn was sung one more time. William M. Runyan returned home to Kansas and died a few months later—but his song lives on.

Why? With the thousands of worship songs that have come and gone in the past 100 years, why do people still remember “Great Is Thy Faithfulness”? And why does it continually resurface during times of adversity and sorrow?

Such was the case in 1956, when a national tragedy sidetracked what was planned as the Jubilee Anniversary of Founder’s Week, the pretext for Runyan’s curtain call. Three weeks earlier, five American missionaries had been killed in Ecuador. The heartbreak hit close to home; all five were Wheaton College graduates and well known to the Moody students. In the days following the news, more than a few chapel services ended with a spontaneous institutional lament—“Great Is Thy Faithfulness.”

Then on the opening day of Founder’s Week, Life magazine ran a 10-page article about the murders, accompanied by a blazing headline: “Go Ye and Preach the Gospel: Five Do and Die.” During the ensuing week, the conference speakers found it hard to stay on topic. William Runyan’s song seemed to offer the best answer.

Thou changest not, Thy compassions, they fail not;

As Thou hast been Thou forever wilt be.

Searching for the true meaning

My own interest in the song came in the usual way—I grew up singing it in church. The congregation sang it for our wedding in 1985, and a family friend made us a calligraphy version, still hanging in our bedroom. I thought of it as an anniversary hymn, celebrating the happy times of life. How little I knew! As life rolled on and I kept singing, I understood it differently, which provoked a new interest in the song itself.

When songs do their job, they burrow into our brains in complex ways. Worship songs connect to our intellect, yes, but also to our spiritual lives and our emotions. Experts struggle to describe how this happens (cue up the music geek’s “explanation” of harmony and iambic tetrameter). Or writers conjure up inspirational song stories about the power of music, supported by sketchy details from the internet. If you’re picking up a bit of skepticism in my voice, you’ll understand why I went on a multi-year trek to understand “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.” The search led from library archives to family scrapbooks to long-forgotten recordings. And along the way I met interesting old timers, a few of Runyan’s great-grandchildren, and some surprises.

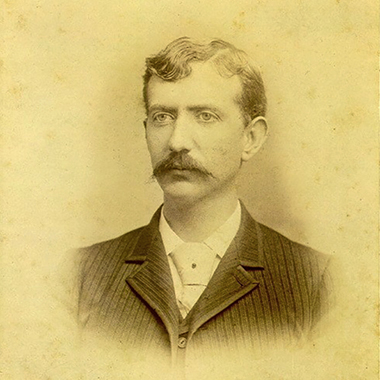

Thomas Chisholm (left) and William Runyan in their early ministries.

Inspired by sadness

As it turns out, the song itself was born in sadness, and came to popularity during a succession of difficult moments. Back in 1923, William Runyan found himself at a personal low point. After studying at Chicago’s Northwestern University and spending 10 years as a Methodist minister, he became a traveling evangelist. But preaching in the pre-microphone era took its toll—after 20 years, his voice was shot. Years later he recalled how he stepped to the pulpit one night and nothing came out—and that was it. Then he became progressively deaf, for which doctors told him there was no cure. For a while he tried a megaphone device that wrapped around his ears, a crazy gizmo straight from the Sears catalog, but not much helped.

A Methodist governing board evaluated the situation and ruled him “non-effective,” the awkwardly named classification that granted him a modest disability pension. But the process exhausted Runyan, who bristled at the non-effective label (“My soul-saving campaigns resulted in more than 800 conversions” in the past year,” he wrote to a friend).

So Runyan turned to his other passion, his talent for editing, a job he could do with his limited hearing. He took a job with a denominational magazine, then started work on a hymnal project, putting out notices that he was interested in purchasing new song lyrics. Meanwhile, in Vineland, New Jersey, Thomas Chisholm caught wind of Runyan’s project and mailed him a stack of a dozen poems.

They had never met—and later, neither could remember any special details about the song’s creation. No inspiring origin story here, which disappointed later researchers who uncovered a pretty boring story: Runyan sifted through a dozen of Chisholm’s poems, picked out his favorite, and wrote a tune. That’s it.

Despite the humdrum beginning, Chisholm’s text drew the two men together in uncanny ways. Though separated by half a continent, both had suffered personal tragedies that felt remarkably similar. Chisholm was a news editor who suffered a breakdown after his mother’s death. (“Mr. Chisholm is mighty low,” his newspaper reported in 1890, not quite knowing what to call it.) He recovered enough to study for the ministry and became pastor of a Methodist church. But his health problems returned and he was forced to leave after only a year. Already in his 50s, having lost two careers because of ill health, he struggled to support his family. He started a business selling life insurance to pastors, and tried submitting poems to various magazines. Sure, he was “inspired,” but he also needed the money.

Runyan’s new career as editor and songwriter attracted the attention of Moody Bible Institute, who hired him in 1925 as editor for their publicity department. One of his jobs was to write the long-running “Moody Alumni” column in Moody Monthly magazine. And his second skill—hymnal editing—resulted in The Voice of Thanksgiving No. 4, which became Moody’s official chapel hymnal in 1928. Runyan included six of his own songs, including his personal favorite, the Faithfulness Song (both writers used this title in their private correspondence).

Which came first—the song, or the tragic moments that ensured its legacy? It’s hard to say, but it’s probably no coincidence that the song rose to prominence during the Great Depression. The stock market crash created great hardships in the student body, and also threw Chicago’s hymnal industry into a tailspin. Often strapped for cash, Runyan approached well-known publishers and offered to sell his favorite song. With no success. One publisher bought three other Runyan tunes for $10 each, but didn’t think the Faithfulness Song was worth the price. Not worth ten bucks!

Worries piled on worries. “My deafness has become steadily more pronounced,” Runyan told a friend in 1930, concerned that the progression “must in time deprive me of any gainful occupation, unless the Good Father shall mercifully order it otherwise.”

George Beverly Shea at WMBI studios; label from first commercial recording.

New popularity

The song story might have ended right there, but one man held a different opinion. In November 1934, when the Depression lingered at its lowest point, Dr. Will Houghton became Moody’s new president. He loved Runyan’s hymnal and loved the Faithfulness Song, believing it to be the right message for hard times.

All I have needed, Thy hand hath provided.

“Great is Thy Faithfulness,” Lord unto me.

More bad news poured in, just a month after Houghton took office. Word came that two Moody alumni, John ’32 and Betty Stam ’31, had been killed by Communist soldiers in China. During the next few weeks, Houghton responded with chapel sermons and impromptu prayer services. According to his father, John Stam had claimed Lamentations 3 as a favorite Scripture passage, and “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” as his favorite hymn. And now the song took on a life of its own. If Houghton forgot to call for it at the end of a service, students started singing it anyway, as a spontaneous benediction before returning to class.

Houghton promoted the song wherever he could. When he hired gospel soloist George Beverly Shea in 1938, he asked Shea to learn the song and feature it on WMBI, where it quickly became a listener favorite. A Moody radio ensemble made the first commercial recording in 1942, followed by many others. Later, as Shea began traveling with Billy Graham, the evangelistic team took the song on its 1954 tour to Great Britain, and from there it spread all over the world.

From the Archives

Summer and winter, springtime and harvest—no matter when it was sung, people remembered. It seemed like everyone had a story, that moment when the song managed to explain life’s challenges in a personal way.

A few years into his presidency, Will Houghton fell sick and suffered through a long hospitalization. When he returned to Moody’s chapel service after several months away, his first order of business—no surprise—was to request the Faithfulness Song.

Rooted in Scripture

What kindles our emotional connections to the song? A good place to start is Chisholm’s text, which draws heavily from Lamentations 3:19–24. The prophet Jeremiah grieves over Babylon’s destruction of Jerusalem, but concludes his litany of bad news with a famous hymn of praise. Chisholm added another quotation from James 1:17, “there is no variation due to a shadow of turning.”

Chisolm never intended his text to be a happy-time platitude, a frivolity to pull out at Thanksgiving time for the annual “count your blessings” service. No, he was acutely aware of the controversies of his own era—he was writing in the middle of a hymnal war. Some of the most famous revivalists had soared to popularity with song books full of shallow lyrics, songs about brightening the corner where you are and hearts wearing rainbows. Somewhere along the line, the gospel had disappeared from gospel songs. Chisholm wanted something different, a substantive song that would respond to his own despair—a testimony of the hope he had personally found in Jeremiah’s lament.

So while the church musicians argued over the merits of “objective” hymns vs. “subjective” gospel songs, Chisholm waded into the controversy by writing a song that stood squarely in the middle. He believed it was possible to combine elements of worship with elements of testimony, that both ideas could exist side-by-side. Of course this idea was not new—his example came straight from Scripture.

Lamentations 3 begins with a first-person testimony (“I am the man who has seen affliction”) and moves to an objective hymn of praise, expressed from a subjective point of view (“The Lord is my portion,” says my soul, “therefore I will hope in him.”)

Thus was born Chisholm’s most famous line, a happy marriage of objective truth (“Great is Thy faithfulness”) and subjective testimony (“Lord, unto me.”).

Chisholm’s friends understood what he was trying to do. “His aim in writing is to magnify the Word, incorporating as much Scripture, either literally or in paraphrase, as possible,” Charles Gabriel once said, “And to avoid any flippant or sentimental themes, choosing subjects from the inexhaustible storehouse of the Bible.”

Runyan agreed, telling a reporter that “new gospel songs with true depth and meaning—songs that stick to the spiritual ribs—are one of the most apparent needs in the world today.” And ever the editor, Runyan obsessed over the punctuation of Chisholm’s poem. Early printed versions included his careful quotation marks around every repetition of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness,” reminding the congregation that they were singing the very words of Scripture.

Runyan’s thoughtful ideas about church hymnody earned him another job. After a decade of rest, his speaking voice was returning, strong enough to host a 1939 Radio School of the Bible class on WMBI. He taught about his favorite hymn writers while students listened to the radio, filling out their correspondence course questions.

William Runyan in his office at Moody Bible Institute, 1939.

However it might be analyzed, Chisholm and Runyan crafted a song that stands up to repeated singing, a song that reveals its truth over time as the singers meditate on its scriptural basis.

The three stanzas of the Faithfulness Song are bound together by a Hebrew word for love. Chisholm’s own King James Version translated this word as mercies: “It is of the Lord’s mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not.” But mercies didn’t quite capture the depth of meaning. Other translators have suggested “steadfast love,” “faithful love,” and even “loyal love,” all of which emphasize the unchanging covenant of God. Maybe Miles Coverdale had it best, back in 1535, when he translated the Bible to modern English. No single word carried quite the right meaning, so Coverdale invented a new one: lovingkindness.

Chisholm’s own explanation of the word always started with a testimony: “My income has not been large at any time due to impaired health in the earlier years, which has followed me on until now. Although I must not fail to record here the unfailing faithfulness of a covenant-keeping God and that He has given me wonderful displays of His providing care, for which I am filled with astonishing gratefulness.”

Like other aspects of God’s character—always difficult to put into words—lovingkindess could be demonstrated by human relationships. After all, the Old Testament uses the same Hebrew word to describe the relationship of Jacob to his son Joseph, the relationship of Ruth and Boaz, and even Rahab to the spies who visited her home. God helps us understand His lovingkindness by sending us people who model His love. And for anyone searching for an example of this David-and-Jonathan commitment, look no further than Runyan and Chisholm.

The two friends kept up a robust correspondence and would collaborate on 20 more songs, though none of these would eclipse “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.” When interviewed, they often spoke about their abiding friendship and their admiration for the other. “We sensed affinity in spirit that linked us in spiritual fellowship from the beginning,” Runyan said.

The friendship endured—no, blossomed—through Runyan’s increasing deafness and Chisholm’s increasing blindness. And for anyone passing through the struggles of life, their song offered a hefty dose of lovingkindness, straight from Lamentations 3—a fresh supply every morning.

Eventual success

Throughout the 1940s, the song soared in popularity and achieved financial success, which becomes an interesting story in its own right. In 1943 William Runyan sold his song—finally—to Hope Publishing Co. in Chicago. From the publisher’s point of view, purchasing song copyrights could be notoriously unpredictable. One song out of a hundred might be successful enough to generate any meaningful royalties. Maybe. As a result, the hymnal publishers took to their work like farmers tending a crop—planting seeds, nurturing song writers, and waiting patiently for the returns.

George Shorney grew up in this world. His father and uncle owned Hope Publishing, and George was the heir apparent, so he spent his childhood around Runyan and other hymn writers. By the time George joined the family-owned company in 1958, the Faithfulness Song was everywhere.

“‘Great Is Thy Faithfulness’ is my favorite hymn,” Shorney once told me, a few years before his death in 2012. Then came his funny explanation: “Because it paid for my college education!”

(I loved Shorney’s punchline but worried about including it here, so I recently asked his sons Scott and John for their blessing. They both laughed and said, “Sure—it paid for our education, too!”)

The transaction proved to be successful for everyone. Hope became steward of the song’s print rights, while Runyan retained the performance rights and licensed them through ASCAP, a company that tracked the song’s use on radio, television, and recordings. The quarterly payments rolled in, and after Runyan’s death, the family endowed a scholarship in his name at Baker University.

Meanwhile, the Shorney family proved to be generous caretakers. They also owned “The Christian Fellowship Song” (“God Bless the School”), and for years they allowed Moody to use both songs free of charge. The family also donated hymnals used in Torrey-Gray Auditorium.

One final financial detail might be worth noting. If you notice a surge in new recordings of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness,” there’s a good reason. The copyright expired on January 1, 2019. The song is now in public domain and can be used freely.

William and Lena Runyan with their family, celebrating 65 years of marriage.

Not quite famous

Whatever financial success the song may have enjoyed, Runyan and Chisholm seemed like prophets without honor in their own country. Both were lifelong Methodists, yet their denomination excluded “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” from official Methodist hymnals in 1935 and 1966. Was it a snub? Probably not—might have been the gatekeepers at work, or a copyright tussle, though no one said for sure. As far as the song’s general suitability, both writers viewed their work as an “ecumenical” hymn, in the sense that it could be sung by orthodox believers in any denomination (there was nothing particularly Wesleyan about its lyrics). Eventually, well after both writers had died, their song was chosen for inclusion in the 1989 United Methodist Hymnal (but by that time nearly everyone sang it, even the Anglicans).

Not quite famous, they did live long enough to enjoy end-of-life tributes. Chisholm was honored at his favorite summer haunt, the Ocean Grove conference. Runyan received an honorary doctorate from Wheaton in 1948, followed by the 1956 Founder’s Week tribute at Moody. Both were listed in Who’s Who, both had obits in the New York Times.

And both were the subject of numerous articles, where magazine writers and college professors would press them for dramatic stories about their favorite hymn. They stuck to their story. “There is no special circumstance connected with the writing of this particular hymn other than the fact that Mr. Chisholm and I were devoted co-workers,” Runyan said in 1954. The “special” part was his relationship with his friend.

For as many times as they mentioned each other in print, few people knew the truth. In more than 30 years of friendship and collaboration, Runyan and Chisholm had met in person only once, for a few hours in 1928. Their friendship continued the way it had started, through the postal service, where they shared health problems, financial calamities, family struggles, and the one solution that bound them together: lovingkindness.

Late in life they made quite a pair—a writer who could not see, a composer who could not hear, two close friends who never saw each other.

And when Runyan died in 1957, Chisholm wrote to the Shorneys with a letter of tribute, saying “I think I have never felt more keenly the loss of a friend.”

New versions

Though the song never disappeared from congregational singing, it kept a pretty low profile during the CCM craze of the 1970s and 80s. Then, sometime in the mid-1990s, Christian rockers rediscovered hymns (as the story goes, the last remaining hymnal was found propping up an overhead projector). And suddenly “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” was everywhere, recorded by nearly every contemporary worship musician (more than 500 versions to date). Some performers incorporated the song into new compositions, such as “He’s Always Been Faithful” by Sara Groves, and the recent “Great Is Thy Faithfulness (Beginning to End)” by Jason Ingram and Mike Weaver. Other performers blended the song with their own musical traditions, such as the gospel/opera fusion of Audrey DuBois Harris, sung at Aretha Franklin’s funeral.

With all of the revisions and reworkings, it seems fair to ask if any of them go too far. John Piper provoked a controversy when he wrote two more stanzas to the famous hymn in 2018, taking it in a different theological direction. Critics immediately asked if the original Methodist hymnwriters would have appreciated the new (Calvinist) lyrics: “I could not love Thee, so blind and unfeeling; Covenant promises fell not to me.”

Maybe, maybe not. Runyan and Chisholm would certainly appreciate any pastor who was trying to connect the preaching with the singing. On the other hand—did their song really need fixing?

Thomas Chisholm answered this question years ago, when he revealed that his original text—the typewritten sheet he mailed Runyan—had been four stanzas long, not three. “Mr. Runyan also improved the hymn by cutting off one of the verses,” Chisholm said. “It was a happy change, for the extra verse would have diluted the message and weakened the unity.” Both hymnwriters agreed that the song was perfect with three stanzas—and apparently agreed to destroy the fourth stanza, which no one has ever located.

Like all classic songs, “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” is sturdy enough to survive a bit of modern tinkering. And like all classic songs, the new versions rarely eclipse the original.

Favorite renditions? Runyan always believed the Moody students sang it best. “That wonderful student body sings the stanzas of the Faithfulness Song with hardly the need of an open book,” he said in 1949, adding that their singing came “from the heart and from experience.”

While finishing up my research this spring, I had a random “Moody moment” on the way back to my office. Four students stood inside the Crowell Hall arch, hymnals open, singing the Faithfulness Song for no particular reason, other than its devotional value. No explanation needed, “from the heart and from experience.”

No matter the difficulty, the song offers a fresh supply of lovingkindness each time it is rediscovered. From the back of the room, not on the service order, comes a burst of spontaneous singing, led by anyone who cares to insert a hymnal commentary on the events of the day. On campus, the song serves as a therapeutic catharsis for hard times—a 2018 prayer revival, on Dr. Paul Nyquist’s last day as president, after the shocking news of a Moody Aviation crash. And it also marks the happiest occasions, such as the prayer service on Dr. Mark Jobe’s first day and his presidential inauguration a few months later.

No one can put into words all that we are feeling; no one can know what the future would hold. But we can sing:

“Great is Thy Faithfulness!”

Morning by morning new mercies I see!