FLASHBACK: Remembering a Bold Voice

- June 9, 2021

When Moody hired William L. Banks in 1970, everyone acknowledged that his appointment was overdue. As Moody’s first full-time black professor, he campaigned for new courses to better represent black churches. Describing himself as “a black evangelical who holds to a premillennial, dispensational interpretation of the Bible,” he was ideally suited for his new role—seminary degrees, pastoral experience, and a gifted writer.

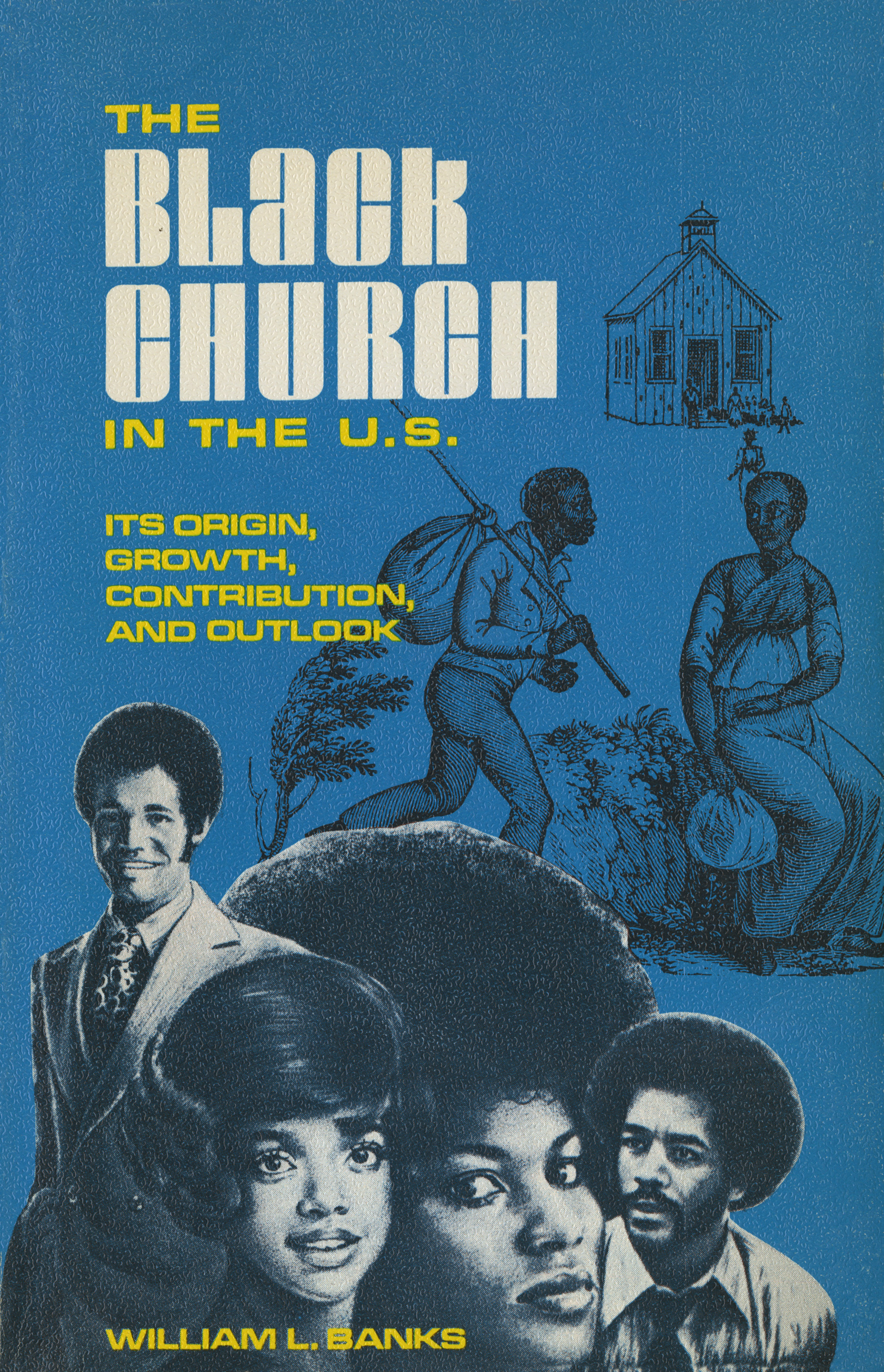

Most of his first semester was absorbed by a full teaching load, but he also volunteered for a passion project. Pastors and ministry leaders were way behind in understanding the black church, Dr. Banks said, so he started teaching a new course in Moody’s Evening School. Of course there was no textbook, so he wrote one, published as The Black Church in the U. S. (Moody Publishers, 1972). The book’s influence cannot be overstated. Nearly 50 years later, Dr. Tony Evans still quotes it as the first major statement of black evangelical thought.

Behind the scenes, Dr. Banks encouraged and prodded Moody administrators to make hard decisions. In one notable instance, Dr. William Culbertson had invited Dr. John R. Rice to speak at Founder’s Week. But then Rice published an article defending the racial segregation of Bob Jones University—and Dr. Banks knew it was time to make a stand. After privately appealing to Rice and Jones Jr., Banks took the matter back to Moody’s president and urged him to reconsider. Culbertson agreed, and sent Rice a forthright response: “Our invitation now gives the impression that the Institute agrees with your views in this regard. This cannot be. Therefore I must cancel out your appearance at the coming Founder’s Week.”

Rice should have let the matter drop, but instead he doubled down and started a writing campaign. The whole issue was a snub over fundamental doctrine, Rice said, and implied that Moody was going soft. The bandwagon letters came flying in from Rice’s friends—a four-inch stack that Culbertson never showed Banks. And although Culbertson didn’t talk about his backup plan, he typed a memo to cancel Founder’s Week, believing it would be better than capitulating on a crucial issue.

Then came a second wave of letters, this time from Moody graduates, affirming the principled stand and encouraging further progress in racial reconciliation. Soon after the flap in 1971, Bob Jones University changed its segregation policy and admitted blacks. Culbertson tossed his memo into a folder, unused, where it was discovered 50 years later in the Moody archives. After several years of teaching, Dr. Banks returned to Philadelphia to serve as a pastor, where he ministered for the rest of his life.

Dr. William L. Banks passed away from complications due to COVID-19 on April 19, 2020.